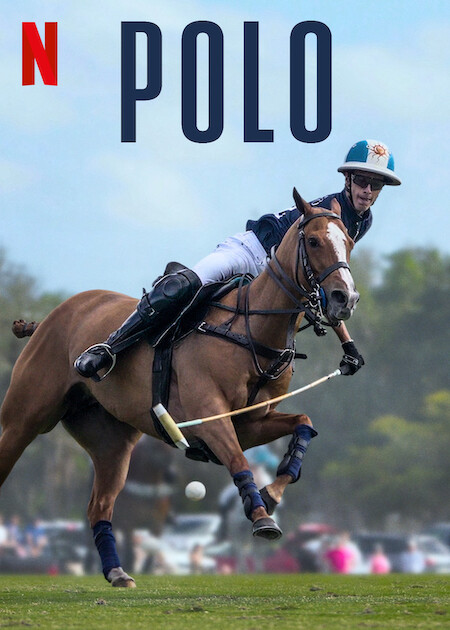

POLO. Netflix series, 5 episodes. 2024.

“POLO” is a five episode Netflix series that is part documentary and part reality show, featuring American and Argentinean players competing in the three most prestigious American polo events, culminating with the US Open held in Wellington, Florida.

POLO (their capitalization) performed disastrously in the Netflix ratings. The British reviewers universally give it a 2/5 rating, describing it as “boring” and “impossible to relate to”. The Guardian called it “unintentionally hilarious”. Virtually no one saw it: even journalists found it such an onerous task that they warned that they “saw it so that you don’t have to.”

POLO begins with a hypothesis: that polo is more family-oriented than is popularly assumed, a concept which has surely preoccupied no one else on Earth. Who cares, truly, one way or the other? “Polo can take a toll on your family,” sighs one WAG (wife and girlfriend). What about garbage collecting? Any toll there?

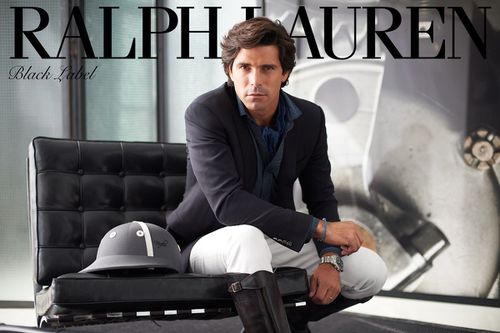

Argentinean player and Ralph Lauren model Nacho Figureas explains that “polo is a lifestyle: you eat, sleep, and breathe polo.” This results in players who are significantly less interesting as people than you might think.

The Americans are the underdogs. The Argentineans, with their superstar model-handsome athletes, play with great competence, showing off magical passes and goals. Historically, they have won trophy after trophy. But it is the stories of the less-famous Americans that dominate most of this series.

The polo takes place in a necessarily closed world, a frenzy of activity in front of a yawning American mouth.

The millionaires and their WAGs are spectators and participants, but certainly represent nothing that would qualify as actual society. The days of the Whitneys and the Vanderbilts, “gentleman sportsmen” picking up a mallet, ended in the 1920s-1930s. Polo shows up how meaningless the words “American aristocracy” are. Polo is now a means of laundering American money into piss-elegance.

In comparison, in England, the spectators at the polo include legitimate titled aristocrats, along with British and foreign royalty. The lineage of British polo, imported from the Raj in 1872, includes Lord Louis Mountbatten of Burma, Prince Philip, Prince Charles, and Princes William and Harry. The takings from wins were donated to charities.

Where British polo attracts corporate sponsors like Cartier, Rolex, Mercedes-Benz, and Moët-Chandon, American polo attracts some down-market ones. One notable sponsor, Coca-Cola, sends quantities of cans, presumably to spray in the event of victory. (Hence the name the “Coca-Cola Team”.) Where Brits say “chukka”, Americans say “chukker”.

Much has been made of the identity of the series’s executive producers: Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, the Duke and Duchess of Sussex. Prince Harry was a frequent competitor in his youth, playing in many friendly matches which generated $15M for his Lesotho-based HIV charity, Sentebale. He was known for his aggressive play and talented horsemanship.

However, in May 2010, Prince Harry infamously rode out Drizzle, a 10 year old pony. As Drizzle began to weaken, Harry rode her off the field to change horses, whereupon she immediately collapsed of a heart attack and died.

PETA was onto that episode and began to campaign about the number of ponies throughout the sport who would drop dead on and off the field. (Harry survived that incident through his Jack the Lad persona and the Palace PR team.)

Increasingly, there are complaints that polo is intrinsically cruel to animals, with its high speeds (30-35 mph) and constant changes of direction, resulting in many broken ankles and legs. Polo ponies are trained for as long as five years (“making a pony”), learning to do the counter-intuitive, running toward chaos and not from it.

Incidentally, polo strikes human beings also who are occasionally killed in play. Successful players are like medieval Wound Man diagrams, featuring broken eye sockets, noses, clavicles, arms, hands, wrists, fingers, and lumbar spines. Then there are the pulled groins, pneumothorax and concussions. Even over the course of this program, one player is put into a coma. Human and horse ambulances are at the ready. (He is soon helicoptered to hospital.)

Prior to this series, Meghan’s involvement with polo appeared in a video of her squeezing her way into the centre of the photo call for a victorious four-man team. She then tried to snatch a prize as a prop from the nearest player and he, proving that the age of deference is coming to an end, refused to let it go. Next she is Xed-out by a large silver trophy, brandished by hairy arms in front of her face. She squats to stay in the frame. She is the Yoko Ono of polo.

One needn’t be a prude to be struck by the sheer volume of profanity in this princely production. The air stays blue, “fuck” by “fuck”, for almost all of the series. (In a bid for multiculturalism, a few “puta de madres” are contributed by the Argentineans.)

Of course, polo itself is not without linguistic eccentricities: “unscheduled dismount” (i.e. catastrophic fall), “hooking”, “being well-mounted” or “out-horsed”. But it is the fucks that soon grab attention.

There is a different caliber of fucks between Britain and America. Former New Yorker editor Tina Brown and novelist Martin Amis, both British, would join in conspiratorial fuck-offs in restaurants, faking an American accent, and would wail with laughter. “Fook you.” “No, you fook you.”

In Britain, ‘fuck’ is the birthright of the upper classes, who can relax into a torrent of obscenities, precisely because they have nothing to prove. Attending same sex schools also neuters obscenities because they have no sexual overtones. From American mouthes, fuck is simply seen as vulgar, sexual, with lower class implications.

—————-

Early on, we see the Ghost of Fucks Yet To Come. Timmy Dutta is the 22-year-old son of an often grim Indian polo father. The father, Tim, runs Dutta Corp, which deals in the exceptionally stressful task of shipping live horses around the world. Tim shouts inspirational phrases from the sidelines (“stop fucking around”, “stupid play”, and “hit the fucking ball”). Not surprising, polo is often compared to hockey with horses. Timmy’s idiomatically fascinating admission: “I take my season here very serious. Don’t go out. Don’t party. Champagne’s only for the podium-type vibes. That ideology, right?”

—————————

It is the large and charismatic Louis Devaleix who is the true fuck junkie. Louis, 43, is the full-time owner of “a healthcare software company in the behavioural health space” and is also the patron of the “La Fe” (the Faith) team. His wife, Pamela Flanagan Devaleix, a lawyer and a winner of the US Open’s Women’s division herself, is heavily pregnant. He has two divorces under his belt, both highly contentious.

Polo attracts ectomorphs, with long, slender muscles, but the sheer Herculean mass of Louis is something thing that sets him apart from the other players. Louis is a quarter pounder of a man, a cartoon of an American. (His little boy nailed it: of all the superheroes, Daddy most resembles the Hulk, presumably in size and in personality.)

In polo, the patron is not only the owner of the team, but his ownership permits him to actually play on the team, alongside three professional athletes. (Remarkably, the other three La Fe teammates manage to embrace while on horseback.) Louis is no billionaire bloatus on his team. He is an okay part-time polo player, despite picking up the game at the antique age of 39. He is a truly fine fuckmeister and is presented as a likeable rogue (provided that the divorce testimony of his first two wives is false).

His opening parry is “fuck yeah, baby”, after an employee secures a business deal. When Timmy Dutta mentions that his mother has opinions about the line-up of the games, Louis teases him with, “what the fuck does your mother know?”

The admission that Louis doesn’t even know the names of his ponies is widely criticized in the polo reviews. Polo players are horse lovers, or at least experts. As everyone admits, the horse’s performance is 60-70% of the game. (No attention is given in this documentary to the ponies as individual athletes. Neither is there a basic rundown of the pony’s training and breeding. Thus, 60-70% of the subject matter is missing.)

While not quite of the same caliber as David Mamet in “Glengarry, Glenn Ross”, Louis plays a mean fuck game himself, fitting the word into every few sentences. Think Jordan Belfort in “The Wolf of Wall Street” loosed on the polo field.

Impressively, during a game of ping pong, he produces “fucking shit of your fucking mother” in French.

Disappointingly, the subtitles omit the occasional fuck, which is covered like a piano leg in the Victorian era. One throwaway fuck is all consonants, so fast that it didn’t register, perhaps only detectable by a radar gun. Throughout his segment, Louis plugs away with his countless fucks.

“We have the best chemistry off the field, but it is not working, not fucking working,” he muses after a loss. “I want to blow the fucking team up.”

Louis has a formidable command of fricatives. His fucks run the gamut. They are angry, philosophical, disappointed, matter-of-fact. Is this a gift or a tic? A feature or a bug? To be fair, not a single one of the dozens of fucks refers to the act of congress. They are expletives, not obscenities, certainly passionate.

Louis arrives uncharacteristically late to a match. He castigates himself: “I was, like, fuck, who the fuck does that?” (After being pulled over for speeding topless in a topless jeep, he moans “I am speeding. Not going to make it. Fuck. I’m late. That pisses me the fuck off.”)

After one loss, Louis attacks a drinks cooler and a bright pink marquee with a polo mallet. For a moment, it seems like the marquee might fatally collapse upon Louis, but it held up, one leg bent. Later, he later sits erect on his mount and roars “fuuuuck” to the sky after missing a goal.

Louis Devaleix and his wife Pamela

Louis’s fucks can get downright romantic. Nestling with his wife, Louis descants: “There’s not a day that goes by where I don’t think about that we could have spent more time together. And I’m sure it can be really fuckin’ lonely, and I am sorry for that.”

Polo players are designated by their handicap, which runs from -1 to 10 (the highest). Louis’s handicap is 1, which makes his goal of beating either of the 10 handicap Adolfo or Poroto Cambiasos frankly delusional.

—————

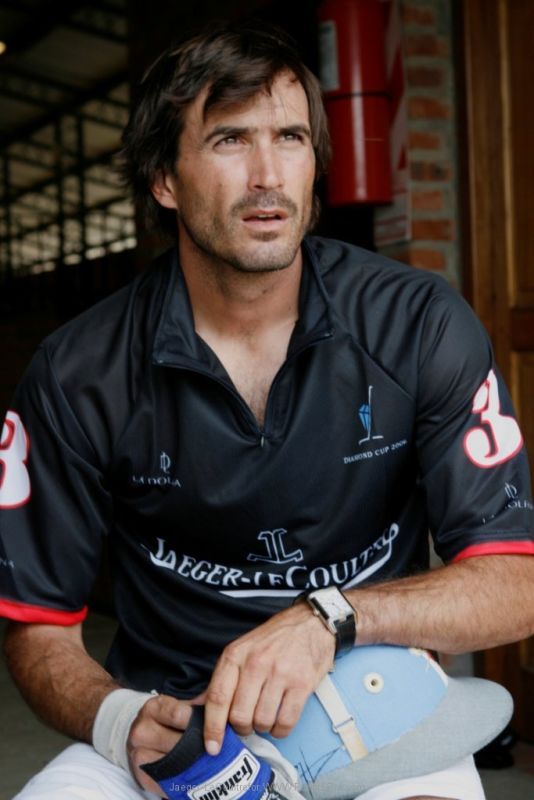

Adolfo Cambiaso of La Dolphina team

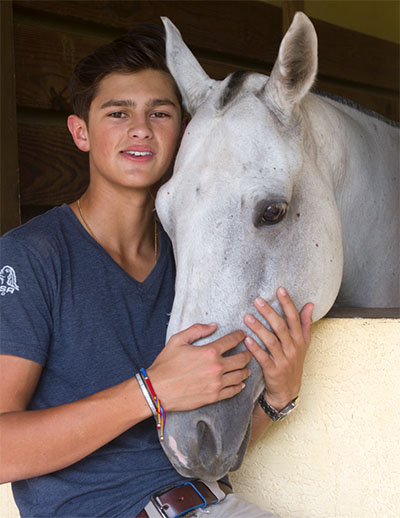

The subplot involves the saga of the Cambiasos, evoking Goya’s painting “Cronus devouring his son”. Father Adolfo Cambiaso was a longtime number one in the sport, and is universally regarded as the GOAT. (“Fuck him”, comments Louis.) But his son, Poroto (aka Adolfo Cambiaso Jr), only 19 years old, is reckoned to be an even greater player than his father. Like a pagent winner eclipsed by her prettier daughter, Adolfo is not completely pleased to have sired such a gifted sprog. Adolfo, 49, who should be retiring about now, plays for Team Valiente and Poroto plays for La Dolfina, so their head-to-head competitions are psychologically charged. “I am proud of my son, but I want to beat him”, admits Adolfo.

Eventually, the son’s La Dolfina team prevails over the father’s team at the US Open, leaving Adolfo muttering unhappily from underneath a towel. This match would have been Adolfo’s tenth US Open.

The missing story here, which is never even mentioned, involves the very controversial practice of cloning which Adolfo Cambiaso began with his two legendary horses, the late Dolfina Cuartetera (2000-2023) and Aiken Cura (1995-2007).

Today, ponies given unsentimental names like Aiken Cura E01 romp to victory. One photo features six Cuartetera clones, who spookily resemble their progenitor and all perform well on the field. There are at least 300 cloned polo ponies in the world, costing only $120,000 each, raising a number of ethical and genetic issues. (Supporting a polo team regularly cost $5-10 million a year, making cloned ponies a realistic option for some teams.) Adolfo is said to own some 1,000 horses, and is always acquiring more.

————-

In the end, it is sad to see Louis defeated. “I’m tired of spending all the fuckin’ money. I just can’t win,” he says, wiping a tear from his eye.

Elsewhere, he sobs: “Had my worst game. Every play, you know, from the fucking beginning. I feel like I’m complete…fucking garbage.” He eventually considers, “Losing is fucking terrible.”

Louis may have written his epitaph: “We went into this game way too confident. It fucked us.”

————————————————————————

For insights on the history of American polo, see:

D.C. Denison, “Polo Makes a Galloping Comeback.” New York Times Magazine (15 March 1981).

Tags: Adolfo Cambioso, Meghan Markle, Nacho Figueres, polo, Porato Cambioso, Prince Harry, Royalty

Lots of laughs, but I don’t think Prince Harry would approve, fuck him

I am astounded how you extracted such a delightful essay from such a terrible show! Netflix should make a documentary based upon your critique of their show. 🙂