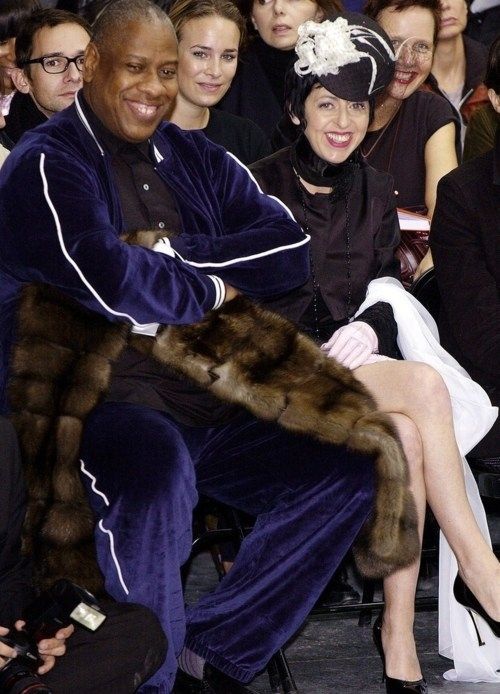

As a young fashion editor, André Leon Talley presented as impossibly tall, impossibly handsome, impossibly well-styled; impossibly observant, impossibly connected; impossibly well-educated, impossibly verbal, impossibly precise; impossibly effusive, impossibly charismatic, and impossibly grandiose. For the comfort of some members of the fashion industry, he seems also to have been impossibly Black. Due to these qualities, Talley arrived (in the old-fashioned sense) everywhere he appeared, usually in the front row, which seated the line of succession of the fashion intelligentsia.

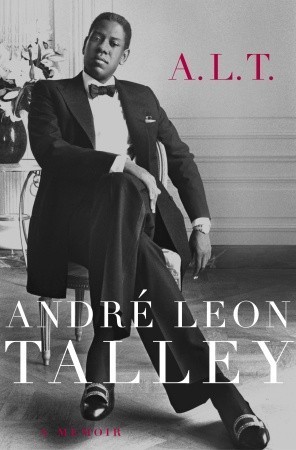

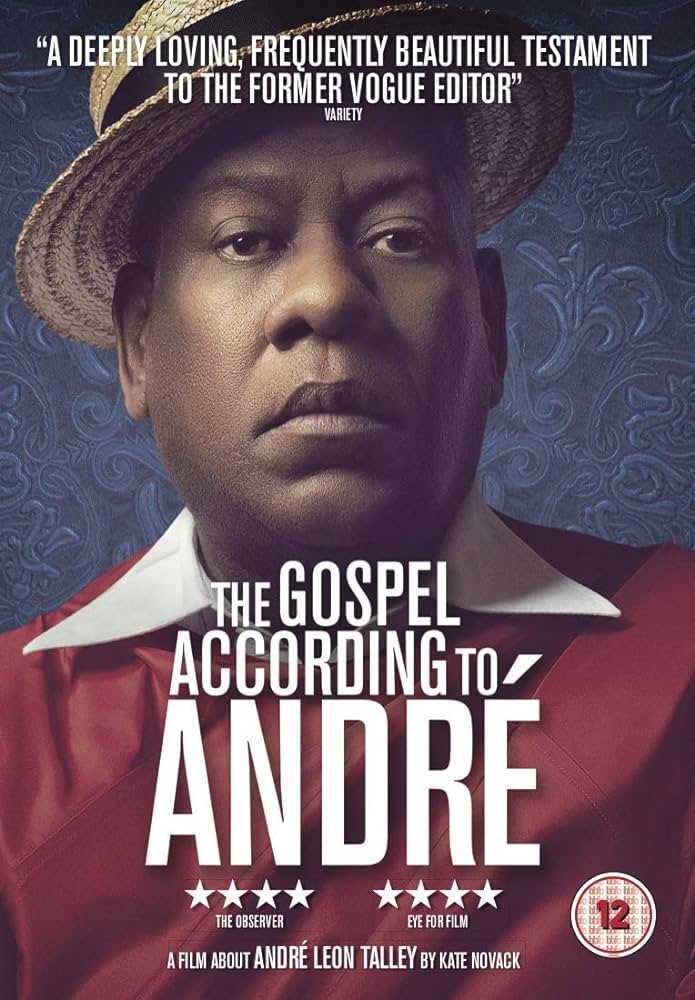

Talley’s death in 2022 of Covid at age 73 depleted the fashion industry of one of its great personalities. This expert-publicizer-editor produced in his last decade a second memoir and a documentary. Following A.L.T. (2003), his second memoir, The Chiffon Trenches (2020), became a New York Times Bestseller, due to its devil-may-care gossip about top editors and designers. The documentary crew for The Gospel According to André (2017) followed him everywhere for years.

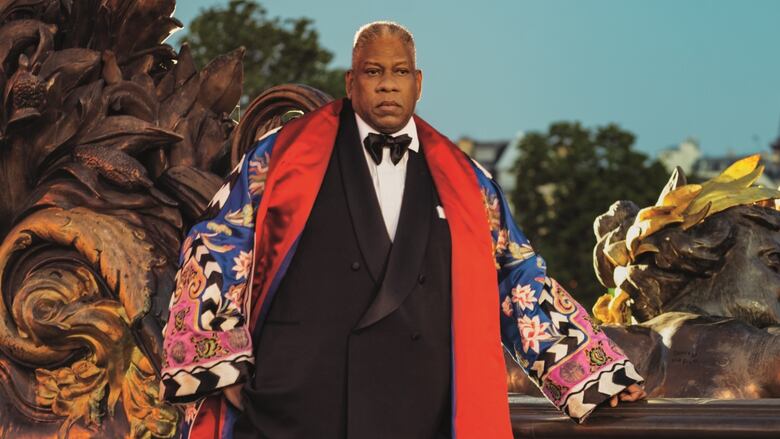

The mother of writer Fran Lebowitz once innocently identified him as her daughter’s friend, “the African prince”. The terms “regal” and “majestic” appear time and again in descriptions of Talley, fashion’s self-made emperor. Talley refers to “being aristocratic in the highest sense of the word. You can be aristocratic without having been born in an aristocratic family.” Even Anna Wintour, editor of American Vogue and one-time friend, acknowledged Talley’s princely air by giving him an African throne.

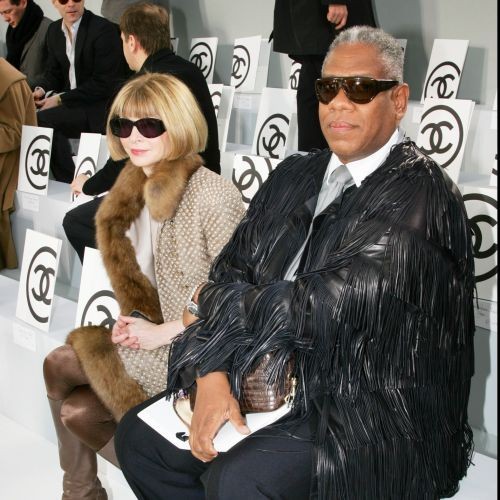

Talley was never a truly dominant force in himself: his power came from his close associations with fashion’s apex predators. There were tender friendships based on arch humour, grand generosity, and intellectual respect. He was, for a time, welcomed, if not truly loved, by Wintour and by Chanel’s creative director, Karl Lagerfeld. In the final years of his life, he was rejected by both without explanation. On more solid ground, he had great lifelong friendships with designers Diane von Fürstenberg and Oscar de la Renta, as well as Lee Radziwill (the sister of Jacqueline Onassis).

He began every morning with an epic phone call with comedian Sandra Bernhard, burning up the wire with gossip and varied observations on contemporary culture. One can only dream of a court stenographer transcribing an anthology of such talk.

The gemlike appraisals never stopped. He sparked magic with his precision tool terminology, his silliness, and his enormous cultural range. He stayed conversant, for example, with pop and rap music, keeping him red carpet-ready for his celebrity interviews at the Met Gala. Parked at the top of the grand staircase, Talley was an institution for many years, shrieking fashion commentary and encouragement to each passing celebrity. Rapper Will.I.am called him “the Kofi Annan of what you’ve got on”. Meanwhile, his substantial knowledge of 18th-century France, which he discussed in fluent French, readied him for chats with Lagerfeld.

Throughout his life, he was all about vocabulary, pinning down fashion frippery with an autopsy of highly technical wording. Manolo Blahnik is the “Bernini of shoes”. Designer John Galliano’s looks range from “zen minimalism to quiet Milanese style”.

Many of his observations were silly but were delivered deadpan. “Do you know how sophisticated it is to match black and navy blue? Most women don’t have the courage.” He decided that “having two bracelets means you’re rich”. He narrated a photo shoot featuring Cindy Crawford walking down the street in Monte Carlo. Here we have “a rich widow in Monaco going to bury her husband wearing a black bathing suit” and a big black veil. Asked why haute couture was not seen in the street, Talley volleyed back “it depends on what street you are on, darling, and at what time of day.”

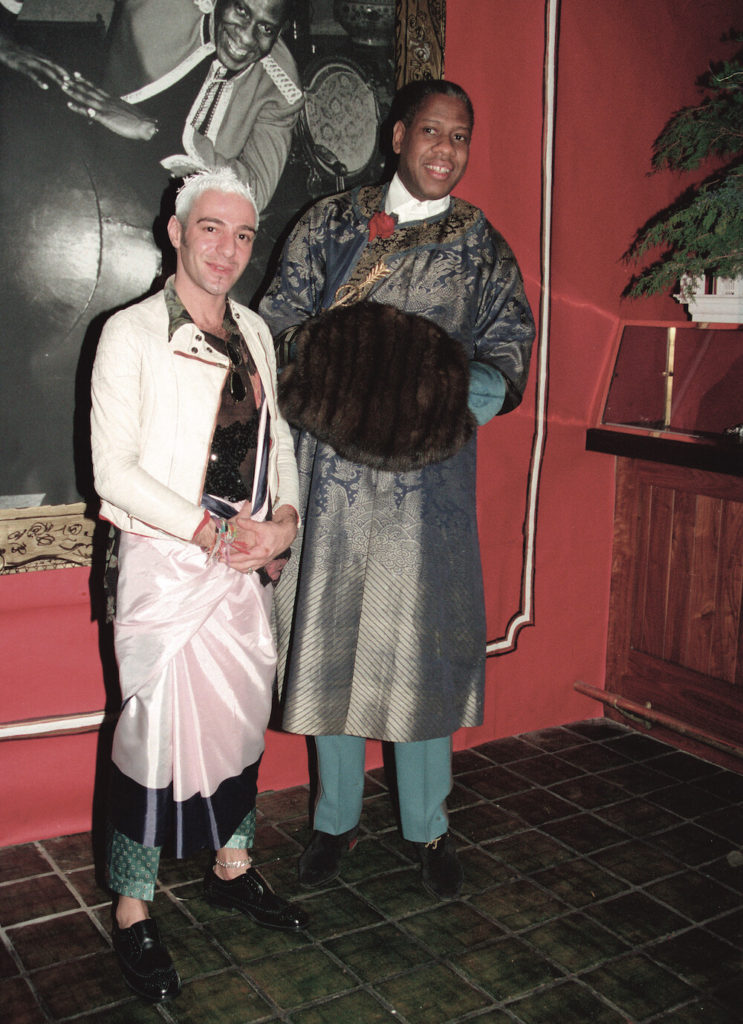

Explaining what fashion meant to him, he erupted with “great excitement, great beauty, great revelment, ravishment, wonderment”. Designer Marc Jacobs described him as an “operatic figure”. Lagerfeld memorably called Talley’s commentary on the shows “a psychodrama”.

His tour at Vogue lasted from 1983-1995 and 1998-2013, with a three year interregnum in which he briefly gave up on Wintour’s coldness. He would also write for Ebony, W and edit for Vanity Fair.

One imagines him a major office distraction, and a murderously expensive one, instilling ADHD in his dazzled co-workers. In the roman à clef The Devil Wears Prada, Lauren Weisberger types all the dialogue for his character in capital letters.

In the days of mid- to late twentieth century publishing, the Condé Nast magazine empire picked up the tab for endless town cars, expensive restaurants, and first class travel as a matter of course. The personnel of Vogue could hardly be seen at a taxi stand, as they are today, according with the collapse of the magazine industry.

Like met like when icon Isabella Blow became Talley’s assistant. An uncanny discoverer of unknown designers, she has been the subject of monographs herself. She washed her desk with Chanel No5, typed wearing opera gloves, and said things like “if you don’t wear lipstick, I can’t talk to you”. On location on a fashion shoot, they squabbled over Blow’s refusal to do a bit of vacuuming. Eventually, he had to fire her after she went AWOL for two weeks on a Scottish shooting trip.

Talley, Blow, and Vogue stylist Carlyne Cerf de Dudzeele were each true characters, all of them genius editors, stylists and oracles. Such was their celebrity that anyone with even a passing knowledge of the industry knew them exactly. Fashion had a great appetite for such one-offs, until the sharky corporate era purged most of them, including, eventually, Talley himself. Blow and Cerf de Dudzeele were both minor members of European aristocracies. The three were each so bizarre, delightful and totally distinctive, that they recall characters from the Muppet Show. Talley was Gonzo, Blow Miss Piggy, and Cerf de Dudzeele Janice from the Electric Mayhem.

He always attributed his success to faultless (retro) manners and to doing his “homework”, which consisted of extensive reading and consultations so that he would arrive at each meeting fully prepared, paying his subject that compliment in itself.

Talley sucked people into a whirlwind of affection and recognition, which one needed a heart of stone to resist. He was charm itself, greeting random strangers with a strobe-lit “hello, how are you”, filled with actual curiosity. His wit and humour attracted new friends. Everyone was always referred to by his title, after years of friendship, (“Mr. Karl Lagerfeld”, “Mrs. Annette de la Renta”) and everyone in Paris was always Madame or Monsieur.

Despite his lifelong celibacy, the “flaw in my life”, Talley loved to love. He was gay, but theoretically so. He attributed his lack of romance to childhood molestation, shyness and his intense concentration on his career. (Talley admitted that he “depended on sartorial boldness to camouflage my interior vortex of pain, insecurity, and doubt.”)

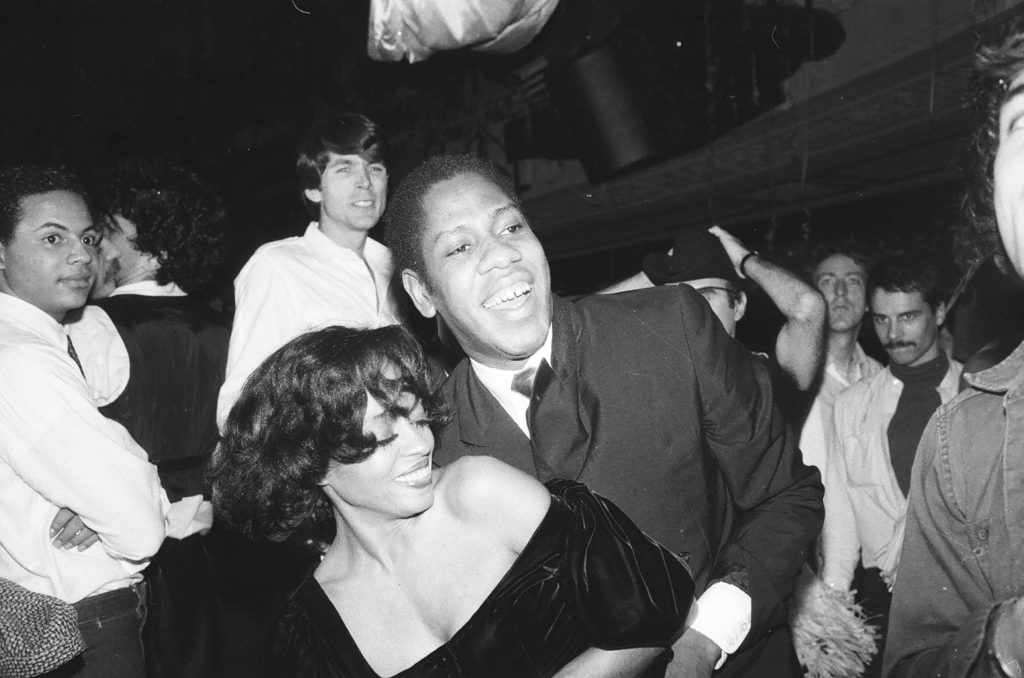

He was, however, promiscuous in his platonic enthusiasms for new acquaintances. He had a special love affair with longtime friends. Talley was a love bomb personified. But Fran Lebowitz called him “a nun” amidst the disco scene of the 1970s, despite his endless nights at Studio 54. He stayed on the first floor, dancing, he explained, while the wildness was played out above.

He subjected every show to his X-ray vision:

“…I learned how to embrace what was going on around me 360 degrees. What makes a beautiful dress? Hems, seems, the way it’s put together. The ruffles. How’s the ruffle? How’s the bow tie? What’s the combination of colours, what’s the combination of fabrics? There’s Mounia on the runway, in what? What was Yves’s [St. Laurent] inspiration? What is the music behind her? What is the chandelier behind her? And there are roses, why are they there? Why is she wearing that shoe? And what is the lipstick? What is going on in the mind of the designer?”

But Talley had a major blind spot in his fashion criticism. He failed to appreciate the disruptive and unprecedented work of Alexander McQueen, the thuggish British designer who frightened Talley at fittings. He would dismiss McQueen’s work as “too dark”. In the end, McQueen’s work was more important than anyone’s of his era.

Instead, he extended himself, time and again, to the resuccition of designer John Galliano’s career, before and after his filmed anti-Semitic tirade that almost destroyed his career. Early on, Talley found him a financial backer who took the Concorde to see his collection. Then, he famously secured the private Hôtel de Luzy owned by an American socialite in Paris, who had a face lift to celebrate. “[Galliano] is a mad poet, like Rimbaud, or Verlaine, or Baudelaire.” At the last minute, Galliano cancelled a trip to the Savannah College of Art and Design to receive the André Leon Talley Lifetime Achievement Award. Talley decided that “Galliano cancelled on Queen Elizabeth II for a state dinner at Buckingham Palace, so it was hard to take it personally.”

Talley’s experiences of overt racism were relatively few, but still searing. Rocks were thrown at him from a passing car when he was a teenager at the Duke campus, making his monthly pilgrimage to buy Vogue magazine.

Clara Saint, a publicist for YSL, was held responsible for Talley’s vile Parisian nickname “Queen Kong”. It is hard to decide whether it is more racist or homophobic. Talley was most stunned by the racism and, in the documentary, his eyes filled with tears when he recalling it. At the time he said nothing.

Talley considered that he might be looked at as “a blackamoor, a black page in a Russian court”. His appearance was such a shock to the fashion world that Whoopi Goldberg called him “the Black Rockette”, who read for viewers as “white-white-white-WHAT?-white-white-white”.

Talley was charged up by the revolutionary appearance of African-American models Naomi Sims and Pat Cleveland in American Vogue, a publication aimed at rich, upper-middle class white women. Also unprecedented was the addition of Mounia, from Martinique, on the runway. Iman, from Somalia, was a revelation, too breathtaking and icily sophisticated for editors to ignore. The Netflix docuseries “Supreme Models” (2025) explains how the appearance of Black models came and went with the seasons. Prada, notoriously, removed all models of colour in favour of sequence of nearly identical washed-out blonde models, so as not to distract from the clothing.

Greatly injured, he resigned in 1979 after being falsely accused by his boss at French WWD, Michael Coady, of sleeping his way to the top of the fashion industry. The accusation was made to Talley’s face in front of the magazine’s staff. He understood that, despite his accomplishments, he was perceived as “a big black buck”, and there was nothing to be done to preserve his dignity but to leave immediately for New York.

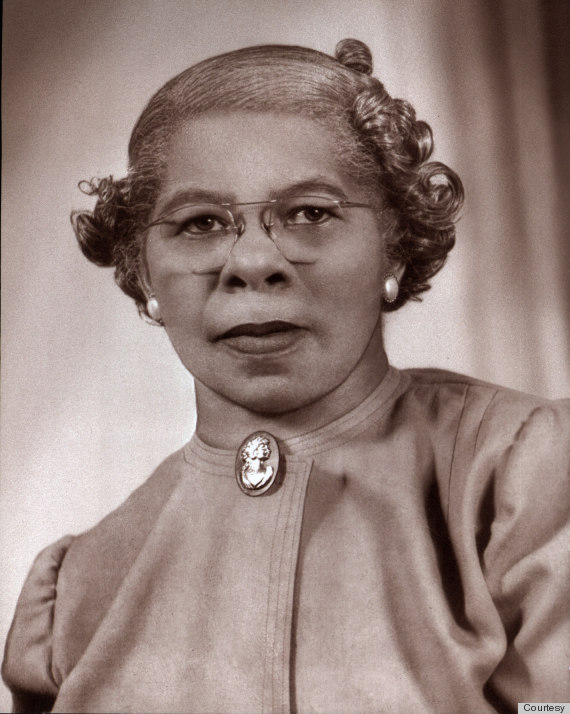

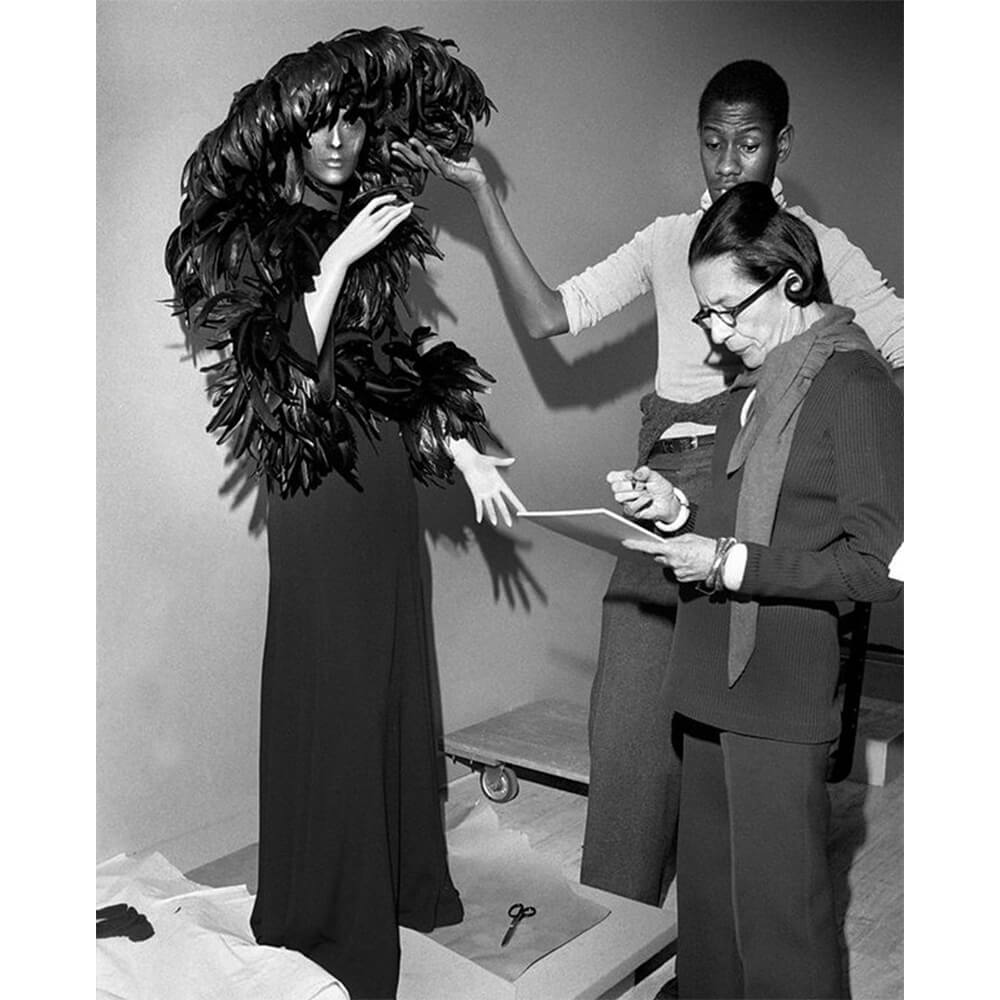

Talley’s origin story revolves around two great ladies, one being his maternal grandmother, Bennie Frances Davis of Durham, North Carolina. The other was Diana Vreeland, the former editor of American Vogue, and the director of the Fashion Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art at the time Talley met her.

Talley’s grandmother, a stern housemaid who worked at a Duke University dormitory, was a personification of the seven capital virtues. He grew up in her imposingly clean and orderly home where he, an only child, was financially supported by her and by both his separated parents. His father was a taxi driver in Washington, D.C. Talley lacked for nothing, and was a great reader who, in his teen years, was already captivated by Vogue and haute couture.

He went on to do graduate work in French literature at Brown University, finishing his masters and dropping out of his doctorate. (His excellent French would eventually lead to a post as the Paris Bureau Chief for WWD.)

Davis attended sermons every Sunday, joining an immaculately decked out congregation, in the great tradition of Black Southern churches. The women each wore wardrobes of gloves, perfectly preserved dresses, and high fashion hats, which they would stack at home in towers of striking boxes. The men wore crisp suits, jaunty hats, and shoes shined buff. This carousel of details and colours provided Talley his first exposure to the concept of fashion.

In an interview with Q, the Canadian arts show, Talley discusses a “moral code to dress well”, to present oneself as best one can, empowering oneself and demonstrating respect for onlookers.

Touchingly, the takings of Christie’s posthumous auction of his treasures, upon which we can imagine he would curl up like the dragon Smog, were divided between Talley’s two churches: the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem and the Mount Sinai Ministry Baptist Church in Durham. The collection included stacks of monogrammed Vuitton luggage, artwork, and a universe of caftans and crocodile coats.

Throughout his life, it took almost nothing to get Talley to start on a long, repetitive monologue about his grandmother’s “unconditional love” and her gift of dignity and correctness. Nearly the first half of his memoir A.L.T. documented his youth in his grandmother’s beautiful, impeccable home. After Talley’s grandmother died in 1989, he seemed to have felt orphaned.

It was from Vreeland he learned his peculiar stuttering diction, each word snapping off his tongue like reins against a horse, his speech made only of exultations and condemnations. His estimations were often delivered in a shriek. From her (and from his study of the television chef Julia Child), he learned a Continental accent. Some called him pretentious, an accusation he simply rejected out of hand, invoking his great artistic scholarship.

Vreeland was a genius and a grandiloquent eccentric. Working as a columnist at Harper’s Bazaar, she wrote a feature called “Why don’t you” that was beyond aspirational— it was thrillingly unrelatable. Her suggestions included “why don’t you turn your old ermine coat into a bathrobe” and “why don’t you turn your child into an Infanta for a fancy-dress party”. She called the all-red room in her apartment her “living room in Hell”. Vreeland was a great practitioner of art for art’s sake.

His internship under Vreeland segued into a dear friendship, when Talley, like a devoted grandson, visited her in her final years and, as her vision faded, read aloud to her newspapers and magazines.

With a little exaggeration, editor Grace Coddington claimed that “André is the only person who has been allowed to see Anna Wintour in her underwear”, another of Talley’s honours. Wintour, a corporate executive, was sometimes uncertain of her knowledge of fashion history and her sense of taste. Talley was essential as a stylist and was required for Wintour’s countless fittings, even as their friendship was falling apart. (Hegel said that no man is a hero to his valet, but Wintour was his hero for decades.) Talley made the mistake of truly loving his reptilian friend.

He accompanied Wintour on countless occasions as her “walker” at fashion shows, conferring upon this white businesswoman a degree of chic. She brought him along as a computer of fashion history whose erudite and nearly deranged thumbs up or down after a show educated her own verdict.

When Talley describes sharing Wintour’s limousine in Paris and Milan en route to the shows, one can’t help but think of The Devil Wears Prada and the fictional editor Miranda Priestley’s final words in her limo. Did Talley listen to Wintour declare that “Everyone wants to be us”? If so, at the time, did he gloat?

He couldn’t speak without name-dropping, but there was pathos in it, as he would descant upon the many honours (opulent gifts, lavish testimonials) awarded to him as self-soothing proofs of devotion. One thinks of the generations of delusional anthropologists writing home excitedly that the natives had accepted them as their very own.

Shot through The Chiffon Trenches was Talley’s pride in being addressed as an equal by the majesties of fashion—Vreeland, Lagerfeld, and Wintour. There is almost no claim too small to be made. Mrs. Eunice Johnson of Ebony magazine would always ensure that his hotel rooms were on the same floor as hers, and Talley doesn’t fail to observe that no other traveling editor offered him this gesture. Renee Zellweger sent him an enormous Christmas wreath. Might he have been considerably more peaceful without taking these measurements and testing these loyalties?

The fashion industry may have invented ghosting. Exchanges of flowers, gifts, and messages on birthdays and anniversaries preserve the balance of terror between fashionistas. Any omission is taken as a calculated outrage. When the gifts and salutations abruptly stop, as they did with Lagerfeld and Wintour, it is like a death.

When Talley first sat with Lagerfeld for Interview magazine, they clicked instantly, and Lagerfeld immediately began to dress Talley, beginning with a gift of armfuls of “beautiful crêpe de chine shirts in kelly green and pink peony, each with a matching scarf”.

Their conversations were so intense one can almost hear the bruit off a still photograph. The two men delighted each other and were the closest of best friends. Lover-like, they couldn’t get enough of each other, having hours-long telephone calls in the morning and evening, when they were not at parties together, faxing, or couriering handwritten letters on luxurious paper back and forth across Paris. Talley received frequent invitations to stay at Lagerfeld’s home, a gift rarely awarded to industry personnel. Even Wintour couldn’t always get Lagerfeld on the phone, and had Talley dial up first.

He luxuriated in his spectacular gifts from Lagerfeld, who made sure to have Talley decked out in Chanel and Fendi. Over the course of their forty year friendship, Talley was also given a black AmEx to cover airplane tickets and long stays at the Paris Ritz.

Talley was never actually dismissed from Vogue nor was he removed from the masthead, but his responsibilities were stripped passive-aggressively, without advanced notice. In 2018, where he learns that he will no longer do his runway interviews at the Met Gala, it is couched as being “beneath him”. He was replaced by a know-nothing young influencer with a vast following.

The final chapters of Talley’s life were about morbid obesity and his insane devouring of “a pan of macaroni and cheese, a pan of turkey with the dressing, stuffing, candied yams, and a basket of homemade biscuits.” He moved from giant to impaired, loudly huffing and puffing wherever he went. His health was shot and Wintour and de la Renta staged an intervention which would have him sent on the next flight to the weight clinic at Duke University. He declined the offer for years.

His weight became an emergency, something impossible to ignore in every encounter. Talley had become the physical antithesis of the Vogue aesthetic. He tried to profit from his enormity with huge capes and caftans in shrieking red and purple, and he often succeeded, as a sheer 6’6” mass of grandeur and authority. An emperor of a sort, he came full circle to his youth, when he was so often described as “majestic”. For Robin Givhan, the fashion critic for The Washington Post, the caftans were “practically paper in their splendor.”

As he became increasingly enormous, he understood too late that he had become a visual liability to his famous friends. The guillotine awaited.

One believes him easily when he says “not a day goes by when I do not think of Anna Wintour.”

Was The Chiffon Trenches a suicide note or the wail “I hate you—Don’t leave me” of the borderline personality? He calls it “a love letter to Anna Wintour”. Yes, he called Wintour “ruthless” and “devoid of simple human kindness”, but he also wrote something like an open letter, a heartbreaking final address to Wintour, to which she never replied:

“My hope is that she will find a way to apologize before I die, or if I linger on incapacitated before I pass, she will show up at my bedside, with an extended hand clasped into mine, and say, ‘ I love you. You have no idea how much you have meant to me.’”